Glandular Fever or Infectious Mononucleosis

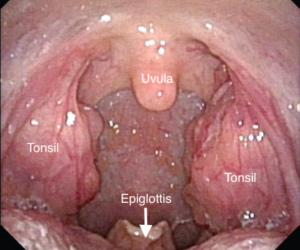

Sore throats are common. As an ENT specialist, I see a lot of patients in our clinics in Singapore with sore throats. Most are thankfully quite mild and need nothing more than lots of fluids, some gargles, and a lozenge! But a few patients have very severe sore throats that linger. When I see a patient with a sore throat, the first thing that comes to mind is whether they may have tonsillitis. And so, the first thing I look at when inspecting the throat are the tonsils. The tonsils are small golf-ball-sized swellings that sit on the side of the throat. They vary in size. The picture below is a picture of a normal throat with prominent tonsils. It is often a struggle to get a patient to open their mouths wide enough for me to take a good look, but this patient was exceptional!

The throat! I have clearly labeled the tonsils, uvula, and epiglottis. The epiglottis is rarely seen in most patients. It is part of the voicebox or larynx

In tonsillitis, the tonsils are swollen. There is severe pain and this is worse on swallowing. Patients often have a fever and are reduced to eating a soft diet or drinking fluids only. Inspection of the tonsils often shows pus coating the tonsils (see picture below). The most common cause of tonsillitis is a viral infection. Viral tonsillitis is mild and often self-limiting. In some cases, the cause of tonsillitis is bacteria. The most common bacterium is a group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus called Streptococcus Pyogenes. This is commonly called Strep Throat and responds well to penicillin-based antibiotics.

Tonsillitis. Note the pus or purulent exudate coating the tonsils. The swab taken from this young lady’s tonsils grew an uncommon bacteria – Klebsiella – so not strep throat!

In older children and young adults, an unusually prolonged episode of tonsillitis with high fevers may occur. The child or young adult is often very lethargic and antibiotics seem to have little effect. These features are highly suggestive of glandular fever or infectious mononucleosis. This condition is also known as “mono” – a lay person’s truncation of infectious mononucleosis.

The term “Glandular Fever” was first used by the Germans in the 1880s. Drüsenfieber was used to describe a condition comprising a sore throat, fever, and painless enlargement of the neck lymph nodes. In the 1920s, Sprunt and Evans published a detailed clinical description of this entity in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. They found an abundance of a subtype of white blood cells called monocytes due to an acute infection – hence coining the term infectious mononucleosis.

Infectious Mononucleosis is due to an infection with a virus called the Epstein-Barr Virus or EBV. This association was only identified much later in the 1960s. EBV is a common virus and in many countries, the majority of children would have contracted this virus by the age of 5. The infection in these young children is often asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. However, in older children or young adults, the infection may take a more severe course. The patient runs a fever, the throat is extremely sore, their tonsils are swollen and there is profound malaise and lethargy. When examined, the tonsils are inflamed and there is often a thick contiguous whitish-grey exudate on the tonsils (see pic below).

Tonsillitis due to infectious mononucleosis. Note the thick contiguous exudate on the tonsils as opposed to the purulent spots seen in a bacterial tonsillitis

Some features are ‘pathognomonic’ in glandular fever and help draw the clinicians’ attention to this diagnosis. The first is the pattern of enlargement of lymph nodes in the neck. These neck or cervical lymph nodes are arranged in groups. The nodes in the front of the neck are commonly enlarged in simple throat infections (pharyngitis) and bacterial tonsillitis. This is often called anterior (front) cervical adenopathy. However, in glandular fever, the nodes in the back (posterior) part of the neck tend to be enlarged. Posterior cervical adenopathy with a sore throat is highly suggestive of glandular fever. Indeed the likelihood of someone with a sore throat having glandular fever is three times higher if they have posterior cervical adenopathy. Doctors often refer to this as a likelihood ratio (LR). Posterior cervical adenopathy carries an LR of glandular fever of 3 in patients presenting with a sore throat.

Clinically, there are a few other signs that point to Glandular Fever. Spots or petechiae on the palate is another key or pathognomonic sign. This has a likelihood ratio of 4. There may also be enlargement of the spleen and liver, and axillary (armpit) lymph nodes.

As an ENT surgeon, my primary focus is often on making a definitive diagnosis. After clinical examination, I tend to take a throat swab to identify a bacterial source and also run some important blood tests. The blood work often gives us the diagnosis. The monospot test, EBV Viral Capsid Antigen (VCA) IgM, and peripheral blood smear are all helpful in confirming the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. The monospot test is very specific. Its specificity is 96-100% meaning a positive test confirms the diagnosis. Its sensitivity is lower at 72-90% meaning a significant number of people with infectious mononucleosis will test negative. I usually supplement the monospot test with the EBV Viral Capsid Antigen (VCA) IgM test which is highly sensitive – meaning it will pick up most cases that the monospot test misses. The peripheral blood smear allows us to look for unusual white blood cells or ‘atypical lymphocytes’. The higher the percentage of atypical lymphocytes the greater the likelihood of infectious mononucleosis.

Several other conditions may mimic glandular fever which are important to bear in mind. The important ones are acute leukaemias and acute HIV infections. In cases where patients are not improving after 3 weeks of treatment, one must question whether the initial diagnosis of glandular fever was correct.

The treatment of glandular fever is largely supportive – meaning lots of fluids and medicines to ease the throat pain and reduce the fevers. Many physicians will give the patient antibiotics to cover any secondary infections, but the truth is that antibiotics are of little value. In medical school, we were taught that the amino-penicillins such as amoxicillin may produce a fine rash if given for infectious mononucleosis. In fact, it was suggested that a fine rash coming on soon after the use of amoxicillin for a sore throat, in a patient not known to be penicillin-allergic, was diagnostic of glandular fever. This is now known to be ‘fake news’ – or at least something not supported by the evidence.

Good intravenous hydration and steroids are helpful. I often use doses of intravenous dexamethasone whilst the patient is admitted to induce remission. I am also a fan of povidone-iodine based gargles as these sterilize the pharynx and are anti-inflammatory.

Patients with enlarged spleens need to be advised against contact sports as there is a risk of traumatic splenic rupture. So no rugby for the teenager recovering from glandular fever or he’ll wind up in the emergency room with a ruptured spleen and a belly full of blood. One can’t stress this enough as the failure to inform patients of the risks of splenic rupture is deemed medically negligent.

It may take up to 12 weeks for patients with glandular fever to regain their strength and vitality! So managing the expectations of a young energetic adult is also very important. Most patients expect to bounce back from a sore throat but this is not the case with glandular fever. The malaise lingers and can often make patients a tad depressed. The good news is that they all recover and are left with no lasting disabilities.

Feel free to email me any questions or comments about this article to drjeeve@entclinic.sg. I am afraid I cannot give medical opinions based on photos of your tonsils but do book in with us if you wish to consult me in any of our clinics in Singapore.

Share this blog via: