For medical professionals: When a sore throat is no better after antibiotics – Laryngopharyngeal Reflux

[This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Medical Connect, a newsletter produced by Eisai Singapore]

Sore throats are very common and make up a substantial proportion of GP visits in Singapore. The most common cause of a sore throat is a viral pharyngitis that will respond well to supportive treatment with analgesics and gargles. A small percentage of sore throats are due to bacterial infections of the tonsils or pharynx. These respond well to penicillin or amino-penicillins. When simple interventions do not work in primary care, the patient is often referred to a specialist.

There is however one cause of a persistent sore throat that is often overlooked and can be treated in primary care effectively. This is laryngopharyngeal reflux or LPR. LPR is a highly contentious condition partly because it has not been accurately defined. Whilst many ENTs will observe the manifestations of this condition and treat it, our gastroenterological colleagues often feel it is over-diagnosed by the ENT community!

Laryngopharyngeal reflux is characterized by the following features [1,2]

- Hoarseness (71%)

- Cough (51%)

- Globus (47%)

- Throat clearing (42%)

- Dysphagia (35%)

A common pathognomonic feature is the occurrence of laryngospasm. The patient often wakes up at night choking and unable to breathe as their vocal folds adduct in spasm. It is a frightening experience but thankfully self-limiting.

Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR) vs Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Unlike LPR which has an array of features, GERD is easily defined by the symptom of heart burn. GERD is due to dysfunction of the lower oesophageal sphincter resulting in the reflux of gastric contents into the lower oesophagus. In contrast, LPR is primarily a problem with the upper oesophageal sphincter. Much fewer episodes of reflux need to occur to result in symptoms as the larynx is not designed to withstand the same level of acidity as the oesophagus. GERD tends to occur when the patient is supine whilst LPR occurs in the upright position – often when the patient bends over or undertakes strenuous exercise. Only 40% of patients with LPR will report symptoms of GERD.

The diagnosis of LPR is difficult. The gold standard is a dual sensor pH probe ideally over several days! In routine clinical practice, where this is not possible, there are two useful tools

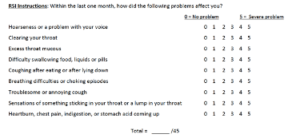

- Reflux Symptom Index Questionnaire

The reflux symptoms index is a validated questionnaire. This is easy to administer in primary care. The short 9 question survey can be filled out as the patient sits in the waiting room.

A score of 13 or more on this questionnaire is suggestive of significant LPR

- Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy is the second tool that is useful in specialist practice. As ENTs, we look for infraglottic oedema (or pseudosulcus), hyperaemia, posterior glottic mucosal hypertrophy and vocal fold granulomas that aid in making a clinical diagnosis of LPR. There is a Reflux Finding Score (RFS) that objectively quantifies the severity of each of these features.

Management

Managing LPR involves a major change in the patient’s lifestyle and diet. These include

- Small frequent meals

- Avoiding strenuous exercise for two hours after a meal

- Reducing spicy, oily and acidic foods

- Reducing chocolates and mints

- Avoiding caffeinated and carbonated drinks

- Avoiding alcohol and cigarettes

- Not laying supine for 3 hours after dinner

When these interventions do not work, the use of a proton pump inhibitor is indicated. The evidence suggests that Omeprazole is not effective in treating LPR. However, Rabeprazole [3] and Esomeprazole [4] twice daily for 12 weeks does improve symptoms. The American Academy of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery recommends 6 months of therapy before weaning the patient gradually over 6-12 weeks. In severe cases, the addition of and alginate (e.g. Gaviscon Advance) after meals and before bedtime is useful.

Who deserves an early referral to ENT (the red flags)

Whilst the majority of patients with symptoms suggestive of LPR can be managed in primary care, there are a few that deserve early referral to ENT for laryngoscopy. These are:

- Patients who smoke and consume large amounts of alcohol, who are at risk of head and neck cancers

- Significant hoarseness, dysphagia or odynophagia

- Associated neck mass

Summary

Do consider the diagnosis of LPR when faced with a patient who has a persistent sore throat and all the key features of LPR. Refer those who have red flag features. Treat the rest empirically with a twice daily dose of PPI and assess response after two weeks.

[1] The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Koufman JA. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(4 Pt 2 Suppl 53):1

[2] Laryngopharyngeal reflux is different from classic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Koufman JA. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81(9 Suppl 2):7

[3] Rabeprazole is effective in treating laryngopharyngeal reflux in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lam PK et. al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(9):770. Epub 2010 Mar 18

[4] Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with esomeprazole for symptoms and signs associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Reichel O et. al. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(3):414

Share this blog via: